|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

Paper by Brian Curtis, Associate Professor, University of Miami, Coral Gables, Florida

delivered at the F.A.T.E. panel Chaired by Alison Denyer at the 2007 Annual SECAC in Nashville, TN |

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

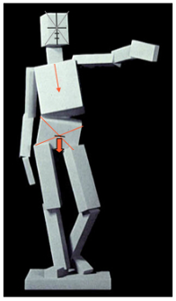

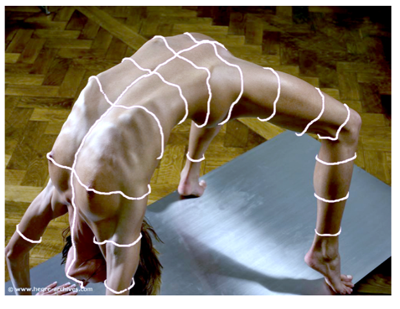

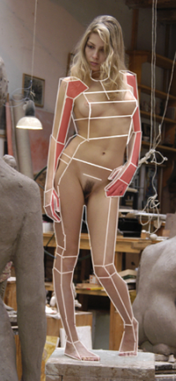

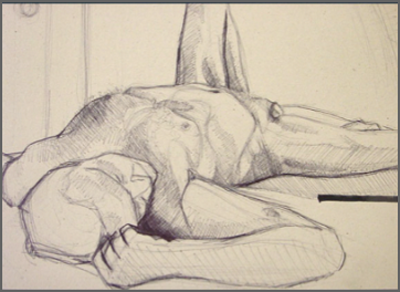

| The pedagogical habitat that once supported longstanding aesthetic traditions and hands-on studio training in the visual arts is rapidly disappearing from the contemporary art school landscape. And nowhere is this more evident than in the increasingly irrelevancy of perceptual drawing/figure drawing in the curriculum of art schools and departments across the nation that are driven by radical theoretical perspectives and digital technology. For over 500 years perceptual figure drawing had been the corner stone of traditional art training.

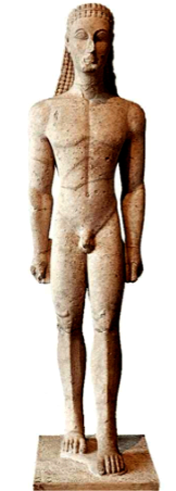

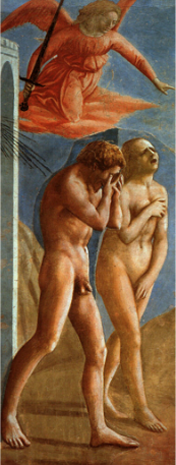

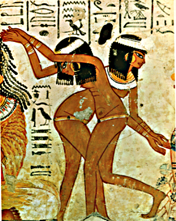

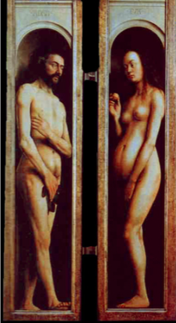

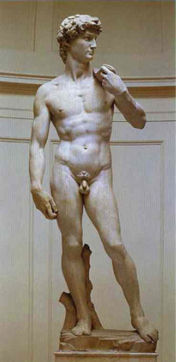

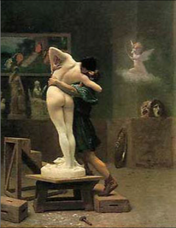

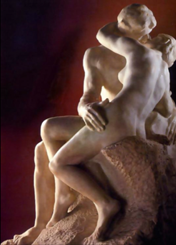

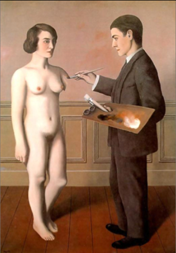

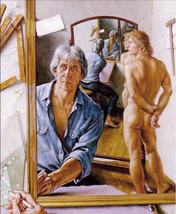

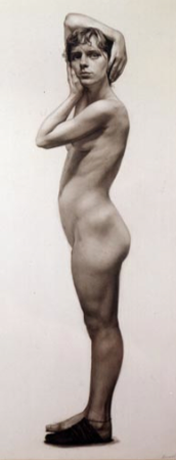

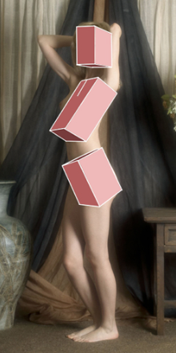

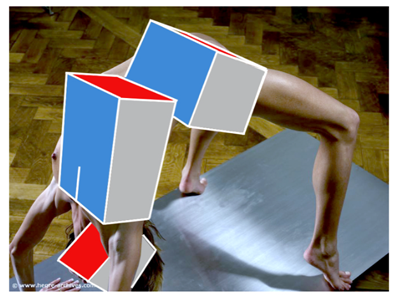

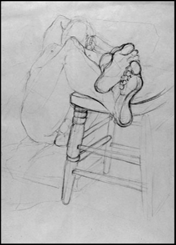

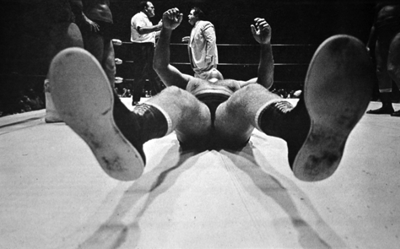

In the last five to ten years, however, we have witnessed a cataclysmic curricula shift in which the longstanding life affirming and life enhancing aesthetic traditions represented by figure drawing have been supplanted by de-stabilizing and de-civilizing forces in the form of digital technology, content driven art, postmodern theory, and pluralism. Debate over the wisdom of radical curricular transformation is a rarely engaged topic at the national level but it deserves to be centrally positioned at the forefront of the discourse of professional artists and educators. In that spirit I am here to give voice to, with apologies to Al Gore, the “inconvenient truth” that our cultural environment is being de-nuded (pun intended) by deliberate destruction of the ideals of grace, truth, and beauty (used without fear quotes), sophomoric attacks on authority, systemic distortions of language and clear meaning, and disrespect for the human form. Let me begin by identifying the de-civilizing influence of the radical theoretical underpinnings of contemporary art. These can be traced back to a variety of closely related sources: to the Dada movement that nonsensically dissolved itself in its founding anti-rational manifesto, to Duchamp’s denouncement of craft and his assault on “good taste,” to the Futurist manifestos’ exaltation of the destruction of the existing order and its re-definition of beauty as political struggle, to Die Brucke’s anti-enlightenment fascination with primitivism, to the many purveyors of shock art from the ‘60’s (i.e. the Situationists International, the dada influenced art group - Up against the wall, Motherfuckers (dada influenced art group connected with the Weathermen and SDS), the conceptualists, Pop artists, performance artists, installation artists, video artists, punk rockers). Each and every of these groups share in sentiments that were given voice in the 1969 counter cultural anthem We Can be Together by the Jefferson Airplane. In order to survive we steal, cheat, lie, forge, fuck, hide, and deal We are obscene, lawless, hideous, dangerous, dirty, violent, and young All your private property is And your enemy is We Everything they say we are we are Up against the wall, Up against the wall motherfuckers These lyrics contain undeniably de-civilizing sentiments that in one form or another have pervaded the art, artist statements, art manifestos and art criticism for the last 35 years. As a result of these sentiments the adjective “transgressive” has become the highest praise that can be bestowed on a contemporary artwork with the understanding that it is always a good thing to violate middle class cultural boundaries. These sentiments presuppose that the middle class is fat, complacent, bellicose, porcine, and deserving of all the abuse the artist can muster and that the artist himself is a transformative and inventive revolutionary who knows the key to the path to justice, freedom, and peace lies in attacking, diluting, and subverting the bedrock of cultural tradition; the social, moral, and aesthetic assumptions upon which our civilization is based. Am I alone in finding this notion to be childishly simplistic? The anarchistic underpinnings of contemporary art have simultaneously been reinforced by a cluster of radical postmodern philosophical perspectives. These radical perspectives embrace the ephemerality, fragmentation, discontinuity, and chaos of modern life and make no attempt at counteracting or transcending them. From radical feminism, gay theory, multiculturalism, to pluralism, deconstruction, and Marxism we are told that there are no longer objective standards to judge anything by and that the notion of aesthetic quality and a singular best is nothing more than a discredited capitalistic white male European “master narrative.” In such a postmodern model the trendy and the tasteless are always better than work based in longstanding tradition and the “rude boy” trumps the skilled hand every time. The second issue I would like to address this morning is the destabilizing, de-civilizing influence of digital technology. The ubiquity of computers makes them the preferred weapon in what has now been a hundred-year war on traditional media. The current pedagogical emphasis on digital media has been greatly amplified by the inherent disdain of radical theory for anything resembling traditional "high art." It should not be overlooked that computers are being promoted as being agents of individual empowerment, democracy, decentralization, and egalitarianism. Unfortunately, however, it is governments and large private corporations that are doing the promotion. That ought to tell us something. According to Neil Postman, a social theorist, the United States is dangerously close to a technopoly. Technopoly is a cultural system in which technology is granted sovereignty over social institutions and national life. It places its faith in mechanical calculation rather than human judgment thereby depriving man of the common source of humanity and leaving him without moral foundation. Rather than decentralizing political power computers and the web are encouraging “stateless” megacorporations by enabling them to “leap boundaries” to intimidate labor unions, elude domestic political opposition, threaten meddling government officials with plant closure and capital flight, and “sidestep regulatory hurdles.” The locus of effective political intervention thus shifts toward more distant power centers. Businesses, moreover, are using computer networks to consolidate high-level managerial control over their expanding global operations and corporations are becoming ever more empowered relative to individual workers, trade unions, and even national governments.” This anti-democratic process has been termed Walmartization and its ultimate goal is a world wide corporate monoculture. On the educational level computers reinforce and compound the unstructured thought processing and learning styles promoted by growing up with TV and now compounded by addiction to computers. Douglas Rushkoff, in his book "Playing the Future", argues that “screenagers” tend to discarded linear logic in favor of a spontaneous outlook that celebrates indeterminacy much the way channel/web surfing does. Both TV and computers expose us to the tyranny of the disjointed moment and bind us to the demons of popular culture and dispirited materialism. What a frightening match for the postmodern anarchical trends I mentioned above, a binary system of pedagogical disruption. For those who would argue that computers help kids learn because they enjoy working on them it is important to remember that when ease and convenience are major factors in determining curricula we are promoting junk learning. When we “dumb down” our expectations to match compromised learning strategies or to match popular culture we are choosing convenience over substance and we are sacrificing the traditional skills of thinking logically, learning to make qualitative judgments, writing clearly, speaking well, developing perceptual and motor skills, and aesthetic sensitivity through hands-on studio training. Without the ability to think rationally and without integrated knowledge that develops from first-hand, real life experience, students are powerless to discriminate the relevant from the irrelevant and the significant from the insignificant in the information glut found on computers. In a fog of techno-euphoria students come to believe that information is knowledge and that digital technology is the only tool they need. In reality they become more passive in their judgments, more alienated from their traditions, more devoid of community. Without this ability to manipulate ideas, “screenagers”, when confronted with difficult challenges, are condemned to a life of rolling their eyes and muttering “Whatever!” Despite the popularity of radical theoretical perspectives and the exalted status of digital technology, there are, fortunately, some among us who still look at these issues from a very different perspective. Ellen Dissanayake, in Homo Asetheticus, presents an intriguing Darwinist perspective on aesthetics that takes serious issue with the postmodernism position that denies the naturally aesthetic part of human nature that has evolved to require beauty and meaning. “Making special is a fundamental human proclivity or need. Aesthetics is not something added to us-- learned or acquired like speaking a second language or riding a horse --- but in large measure is the way we are.” "To make something special generally implies taking care and doing one's best so as to produce a result that is -- to a greater or lesser extent, ---- accessible, striking, resonant, and satisfying to those who take time to appreciate it. This is what we mean when we say that via art, experience is heightened, elevated, made more memorable and significant." In explaining the misguided direction of much contemporary art production she goes on to say; “Much of art today is like the display of a captive lone peacock vainly performed for human spectators, or the following by baby geese of a bicycle wheel instead of their mother. When an animal is removed from its natural milieu and deprived of the cues and circumstances to which it is designed by nature to respond it will behave as best it can but probably in errant ways or reference to aberrant cues and circumstances.” If Dissanayake is correct in identifying essential aesthetic needs, and I believe she is, then it is critical that we waste no time in restoring a sense of proportion to the intellectual, aesthetic, ethical, and spiritual character of art making and art education. I encourage this in the understanding that longstanding culture tradition, far from being the root of evil, is that which gives meaning to our lives. In the words of Theodore Dalrymple (aka Anthony Daniels), “Civilization transcends barbarism. Civilization is the sum total of all those activities that allow men to transcend their biological existence and reach for a richer mental, aesthetic, material, and spiritual life.” He goes on to say, “Art, in its highest expression, explains our existence to us, both particularities of the artist’s own time and the universals of all human history. It transcends transience and therefore reconciles us to the most fundamental condition of our existence. In the history of art, unlike that of science, what comes after is not necessarily better than what came before.” Sometimes the answers to tomorrow’s questions can be found in the past. This is certainly true in art training. I am confident that there is no better course of study for helping to restore the aforementioned sense of proportion than that of perceptual drawing/figure drawing. Perceptual drawing demands active, perceptive sight. It requires both the artist and the viewer to look deliberately, look intensely, seek meaning in experience, and pursue a state of complete awareness of what it is that you are seeing. Figure drawing is unique in its clarity of focus and in its ability to address not only the expressive potential of the drawing process itself, but also to foster understanding of perception, the means of translating those perceptions, one’s own personality, the relationship of the mind and body, and, most importantly, an understanding of one’s environment. And as Walt Whitman wrote in I Sing the Body Electric, "If anything is sacred, the human body is sacred." The importance of figure drawing relies directly on its narrow focus on the human body. Ernst Gombrich, in Art and Illusion, reminds us that “limitation is not a weakness but rather a source of strenght for art.” Figure drawing has also played an exalted role in Western civilization. Quoting Gombrich again, “The hallmark of the post-medieval artist has been constant alertness. Its symptom is the sketch, or rather the many sketches which proceeds the finished work and, for all the skill of hand and eye that marks the master, a constant readiness to learn, to make and match and remake till the portrayal ceases to be a secondhand formula and reflects the unique and unrepeatable experience the artist wishes to seize and hold. It is this constant search, this sacred discontent, which constitutes the leaven of the Western mind since the Renaissance and pervades our art no less than our science.” Well, I can see by my word count that it is time for this voice to stop crying in the wilderness but before I go let me make one last plea for us to stop marginalizing, disputing, and undermining the essential core of our humanity and rededicate ourselves to making our lives more significant through the life affirming traditions among which is the study and artistic mastery of the human figure. |

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

| PRESENTATION INDEX | SITE INDEX | ||||||||||||||||||||

| email: brian_curtis@mac.com | |||||||||||||||||||||

| University of Miami Faculty Webpage | |||||||||||||||||||||