|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

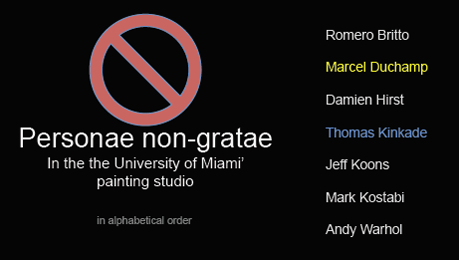

An Unapolegetic Declaration of a "Typical" Elitist Attitude

|

|

|

|

Paper delivered by Brian Curtis, Associate Professor, University of Miami, Coral Gables, Florida

at the 2010 SECAC. Conference in Richmond, VA, October 22, 2010

for a panel titled "Thomas Kinkade in the Classroom"

Chaired by Julia Alderson, Humboldt State University

|

|

|

|

I have come here today to take issue with both the enterprise known as contemporary cultural practice and with the current state of art pedagogy by offering a critical reaction to an essay by Linda Weintraub in which she suggests that the paintings and/or art career of Thomas Kinkade qualify as legitimate content in the training of undergraduate painters. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

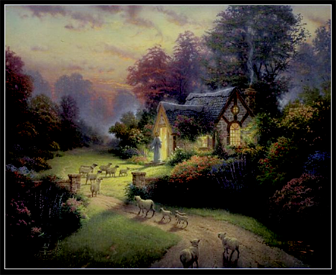

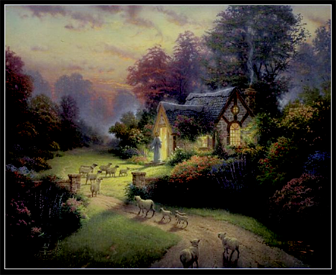

| Jesus and his lambs visiting a Kinkadian fairy-tale cottage at dusk |

|

|

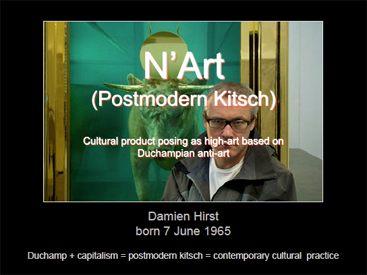

Since I believe that Weintraub's proposition raises more questions about the soundness of contemporary art practice and its underlying premises than it does about this particular painter’s art, I will only invest a small portion of my talk this morning discussing Thomas Kinkade’s paintings and, instead, will focus the majority of my energies on exploring the pedagogical mindset underlying Weintraub’s proposition, a proposition that I will attempt to prove is symptomatic of the widespread aesthetic bankruptcy that pervades contemporary cultural practice, or as I prefer to call it, N’Art. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

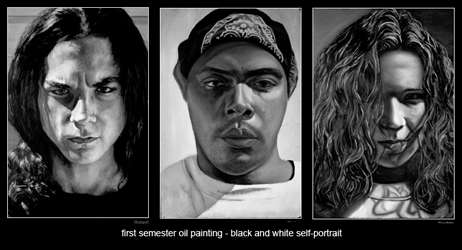

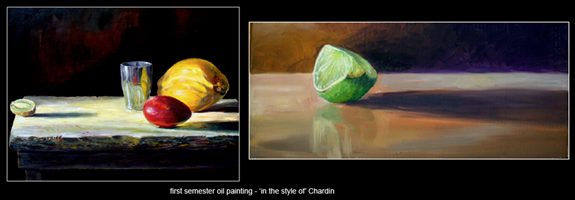

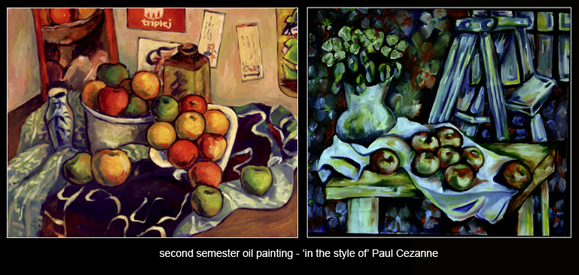

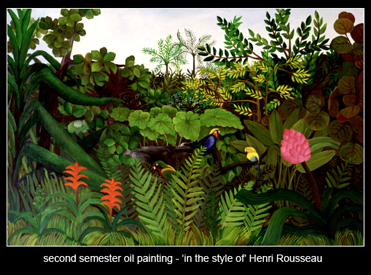

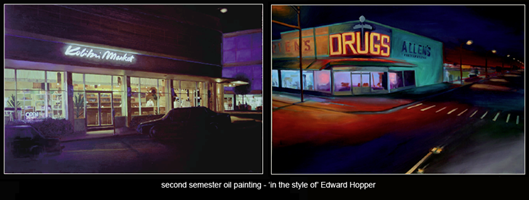

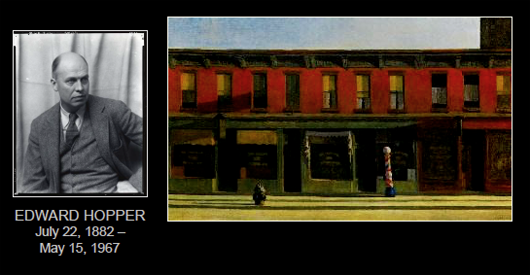

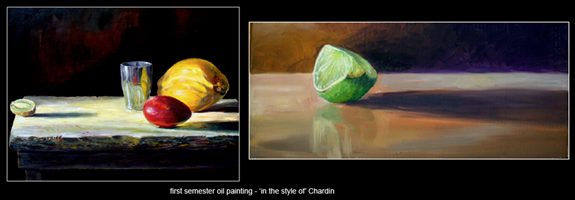

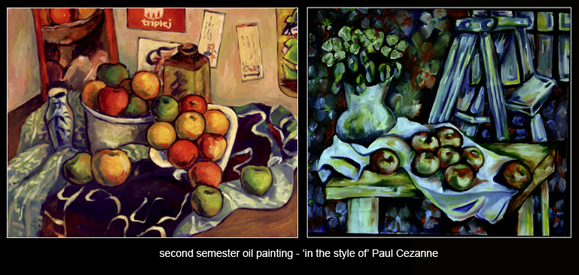

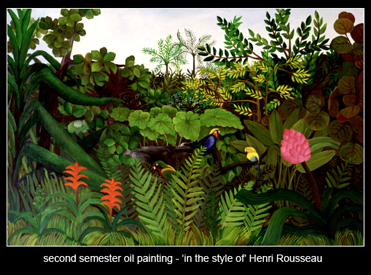

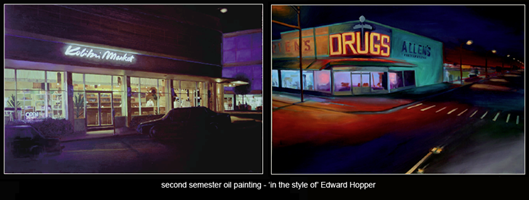

But before enumerating what I believe to be the shortcomings of the language based, post-studio, “post-object model of contemporary practice that valorizes collaboration, social process, topicality, and discursivity” over the evolved human need for a direct intuitive experience of beauty and visual pleasure, allow me to accompany my remarks with a description of the first two semesters of painting as taught at the University of Miami. These painting classes, like all studio classes that I have been privileged to design and supervise, are structured upon a cross-cultural Darwinian model that is firmly rooted in the understanding that the human central nervous system evolved with specific perceptual mechanisms whose purpose it is to organize sensory information into meaningful experience and that, when successfully engaged, produce intense sensory pleasure and profound emotional satisfaction. Despite the fact that we all depend on these perceptual mechanisms to make sense of our environment, the complexity of our fast-paced, high-tech global society makes it all too easy to forget how much we share with our prehistoric ancestors who survived by finding meaning in their environment and satisfaction in the beauty and wonder they experienced. Their genes are our genes and their art instinct is our art instinct. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

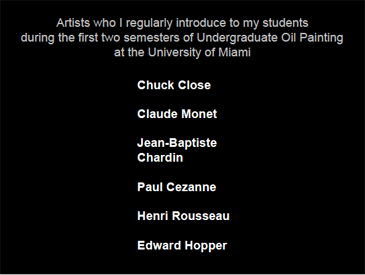

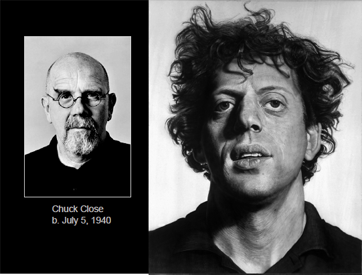

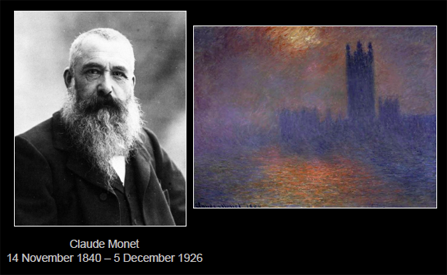

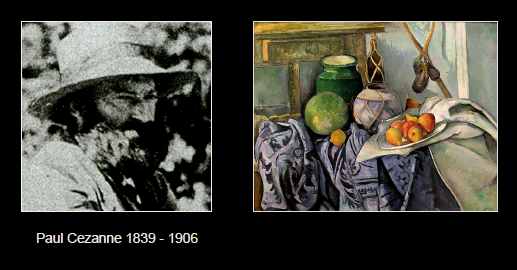

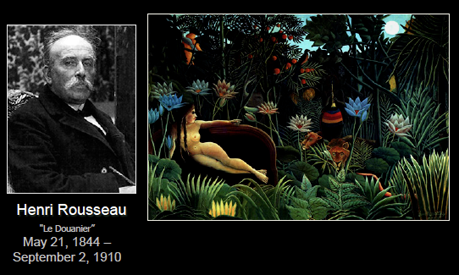

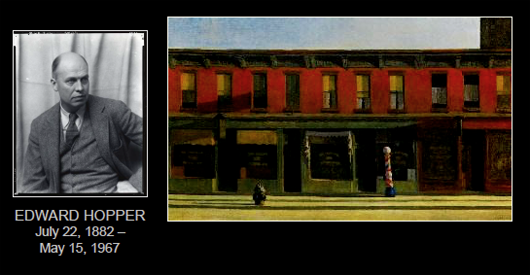

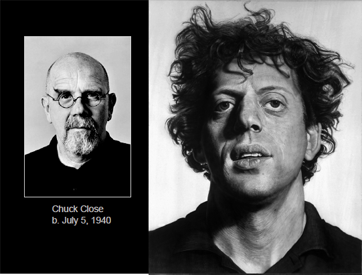

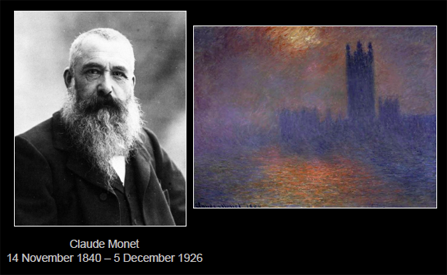

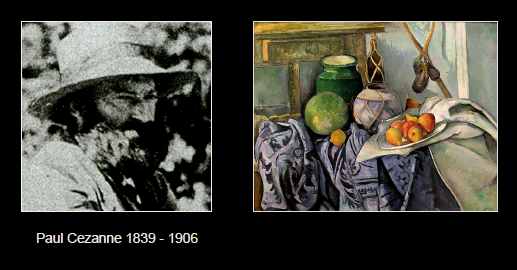

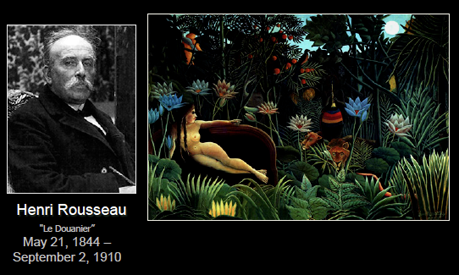

Based in the undeniable fact that the past is a proven storehouse of knowledge and wisdom, I have chosen to structure my first and second semester painting assignments around well-known artists from the traditional canon whose work dovetails with the elements, design principles, and studio practices that constitute a well-balanced foundation in oil painting |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Working with and reacting to acknowledged masterworks is a time-tested process for training the hand, eye, and mind of a beginning visual art student, especially when this training is structured around a carefully sequenced series of assignments that exposes students to historical tradition and focuses on developing aesthetic sensibilities and technical skill by encouraging sustained intuitive and emotional engagement with the assignment being created. Such a course requires a student to look deliberately, look intensely, seek meaning in experience, and pursue a state of complete awareness of what it is that they are accomplishing. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

From a Darwinian perspective, as outlined by Denis Dutton in his book, The Art Instinct, the above pedagogical model springs from an innate human predisposition to value objects that provide direct sensory pleasure, require specialized skill, require a decoupling from practical concerns, logic, and rational understanding, and acknowledge their place in the traditions of art. He goes on to describe art as:

“CHEESCAKE for the mind – delivering a megaWHALLOP of agreeable stimuli concocted to push our pleasure buttons wired in the Pleistocene era. “

In contrast to the traditional studio model upon which my courses are structured, the wholesale curriculum re-definitions underway around the country have purposefully moved away from the Darwinian model and replaced it with a pop-culture lemming-stampede to jettison everything old and bring in anything new. Old is bad, new is good. As a result, the most popular word in contemporary education is innovation. I would go so far as to liken it to an obsession. However, please take a moment to remember that the term innovation, despite its current ubiquity in today’s academic jargon as a synonym for improved, only means “new” or “different” and as the value free term it is, does not guarantee any benefit or improvement. Perhaps some of you will have heard of the Hindenburg, the Edsel automobile, Thalidomide as a sedative for pregnant women, the insecticide DDT, Betamax video format, cold fusion, Ronald Reagan’s Strategic Defense Initiative, or the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. Certainly most of you are old enough to remember the Dot-com bubble, Microsoft VISTA operating system, pre-emptive war in Iraq, financial de-regulation of Wall Street, exorbitant executive compensation, sub-prime mortgages, credit default swaps, and most recently, the Deepwater Horizon’s blowout preventer. Innovations all.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Hindenburg Disaster

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Thalidamide victim

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Flag of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Deepwater Horizon disaster

|

|

|

Unfortunately, curriculum innovations that either have been or are being adopted at art programs across the country are all too often based upon popular-media hype, unsubstantiated facts, poorly reasoned premises, and/or arcane philosophical abstrusiosities. Knowing that innovations can and have in recent memory led to disastrous outcomes it behooves us to proceed cautiously and seriously consider multiple strategies before changing our curricula. It is a dangerous misinterpretation of the maxim that “those ignorant of history are condemned to repeat the mistakes of the past” to suggest that history is only a repository of failed ideas. A corollary maxim reminds us, “those ignorant of the past are condemned to an infinite loop of having to rediscover the wheel.“ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

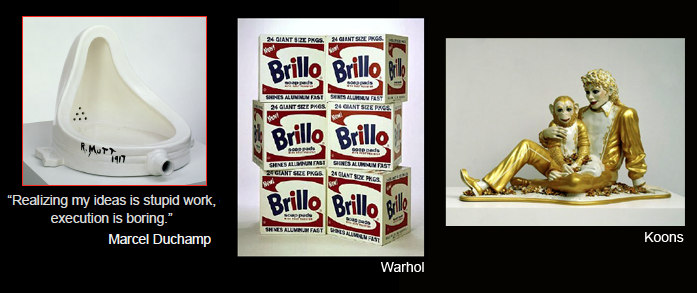

Few today would attempt to deny that the curricula in place at the majority of schools around the country are firmly rooted in de-civilizing, anarchical theoretical perspectives: Dada’s declared determination to destroy traditional culture and aesthetics, Duchamp’s wholesale rejection of “retinal” art, the Futurist manifestos’ exhaltation of chaos, Die Brucke's anti-enlightenment fascination with primitivism, Fluxus’ call for the elimination of illusionsitic art, abstract art, while promoting anti-art and non-art reality, conceptualists, Pop artists, performance artists, installation artists, video artists, punk rockers, graffiti artists, and the variety of other postmodern approaches that have been lumped under the banner of contemporary cultural practice. These assorted perspectives insist that there are no objective standards on which to make value judgments and that the notion that visual quality is discredited capitalistic white male European 'master narrative.' |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

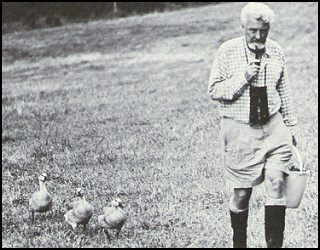

To this litany of postmodern attitudes, Ellen Dissanayake, in her treatise on Darwinist aesthetics, Homo Aestheticus, responds:

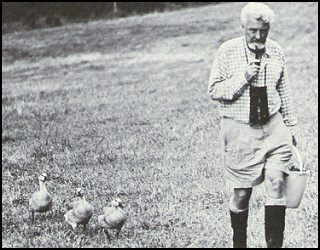

“Much of art today is like the display of a captive lone peacock vainly performed for human spectators, or the following by baby geese of a bicycle wheel instead of their mother. When an animal is removed from its natural milieu and deprived of the cues and circumstances to which it is designed by nature to respond it will behave as best it can but probably in errant ways or reference to aberrant cues and circumstances.”

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Animal behaviorist Konrad Lorenz with baby ducks following along after having been imprinted to respond to him as their mother |

|

|

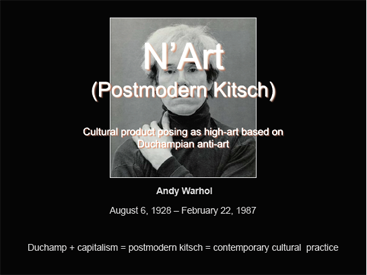

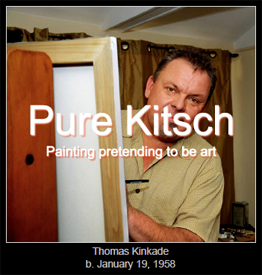

Let us now return to Weintraub’s suggestion that Thomas Kinkade’s paintings are suitable examples in training undergraduate painters. I would like to start by suggesting that Wientraub choose Kinkade, not out of any sincere appreciation of his artistic goals and achievements, but because his kitsch paintings are anathema to high-art’s pursuit of serious content and authenticity. In so doing, Weintraub transforms Kindade into nothing more than a Readymade of Duchampian anti-art. Weintraub is blatantly exploiting Kinkade’s obvious mediocrity to undermine the innate and enduring values of high-art by using it as a weapon in the century-old battle between visual (art) and verbal forms (n’art) of cultural production. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

As Peter Kaniaris, a professor of painting at Anderson University in South Carolina, so cogently observed in an essay titled The Visual Impulse: A Lost Metaphor:

“Rooted in the practice of art is an ancient metaphor: that art is (at its core) an irreducibly visual experience; its “language” and knowledge are unique; its outcomes are like no other outcomes; its value is intrinsically bound to its means. It is a foundational experience that has its origins in the visual impulse, the innate human desire to communicate through visual means. It is the ancient metaphor at work, as old and deep as the paintings of Lascaux.”

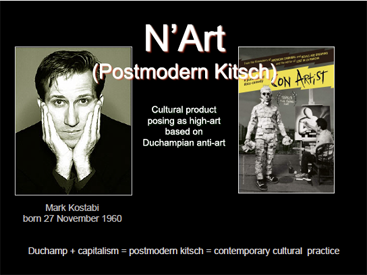

Because Kinkade’s name appears in our panel’s title, I will discuss his works before I conclude today. However, I am confident that both he and his work are utterly extraneous to Weintraub’s thesis. What is actually is at the core the essay in question is the ubiquitous promotion of the legacy of Marcel Duchamp and the continued dissemination of the anti-rational program of postmodern theory where “the meaning of a work of art “is never clear, sufficient, or inherent” but “is always suspended and deferred,” and “what is present in an artist’s mind...does not appear...” in a work of art.

Although my educational training does not qualify me to single-handedly challenge the philosophical premises underlying postmodernism, there are highly qualified experts who can and do. Among them is a renowned philosopher at the University of Miami, Susan Haack who describes the postmodern intellectual climate in less than glowing terms.

“When sham and fake reasoning is ubiquitous, people become uncomfortably aware, or half-aware, that reputations are made as often by clever championship of the indefensible or the incomprehensible as by serious intellectual work, as often by mutual promotion as by merit”

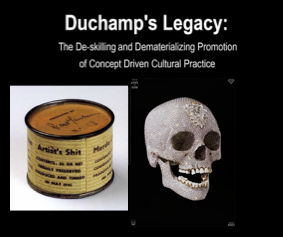

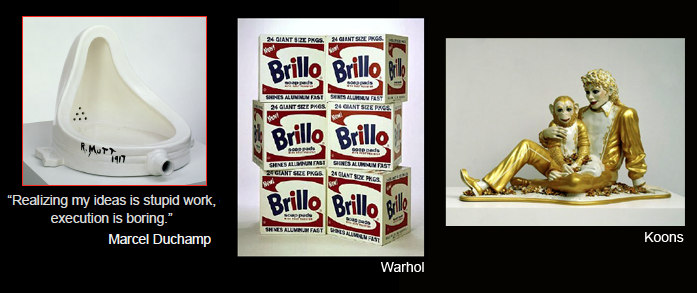

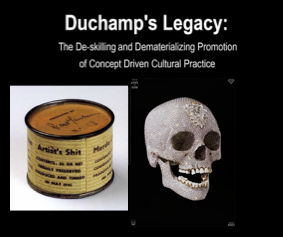

With the support of arcane postmodern theory Marcel Duchamp has become the patron saint of contemporary culture practice, revered for having severed the link between visual perceptual experience and the inherent value of a work of art. Although this “sterilization of the visual” has roots dating back to Plato’s idealism, the current curricular antagonism between visual and verbal forms of knowledge is Duchamp’s legacy.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

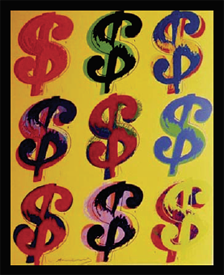

As you might recall from the 2004 survey of 500 British art world specialists, Duchamp’s Fountain (above far right) was voted the most influential artwork of the twentieth century. A curious icon for a bloated, overpriced world art-market that is packed-full of cult-like practitioners of concept oriented cultural practice and one that is incestuously intertwined with our perverted capital markets. Curiously, the original urinal no longer exists because Duchamp threw it in the trash to demonstrate that he had absolutely no interest whatsoever in the value of the object. Duhamp’s influence on contemporary cultural practice becomes even more ludicrous when you consider that he clearly stated that his goal was to “de-deify” the artist and that he unequivocally opposed using art as a commercial venture. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

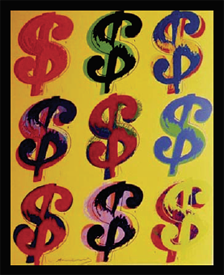

Dollar signs, Andy Warhol

|

|

|

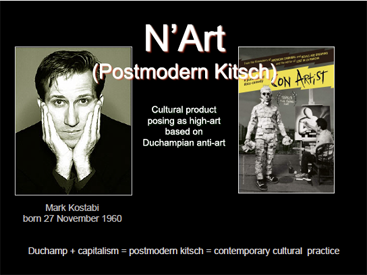

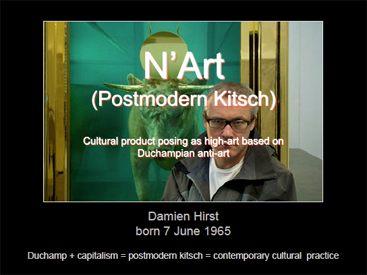

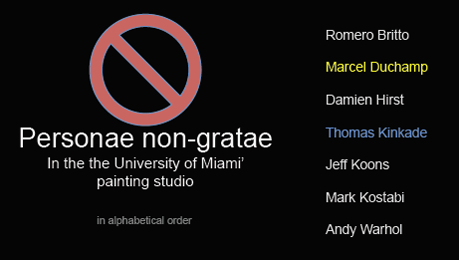

Despite Duchamp’s admonitions we now find ourselves innundated by a flood of Duchampian wannabees. Notorious N’art “stars” like Andy Warhol, Mark Kostabi, Damien Hirst, and Jeff Koons, just to name a few, reverently follow in Duchamp’s irreverent footsteps but lack the integrity and discipline to maintain his anti-bourgeois cultural stance.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

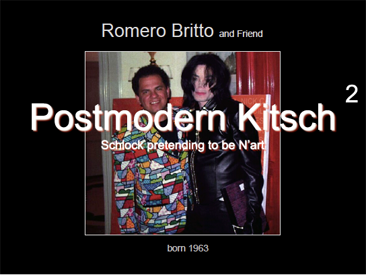

While Duchamp’s anti-art stance inadvertently made him a declared enemy of kitsch (in that his intellectual provocations, in challenging the solemnity and seriousness of high art, cuts the lifeline to which kitsch so desperately clings in its claim to legitimacy), endless numbers of today’s practitioners are demonstrably nothing more than purveyors kitsch, albeit postmodern kitsch. They shamelessly repeat Duchamp’s provocations while brazenly exhibiting their hypocrisy by seeking celebrity and wealth in the all too serious and solemn hyper-commercialized frenzy that is the world art-market – a market that, like the recently failed international capital markets that have severed profits from material production, has separated sensory pleasure from the cultural value of the work. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

One outstanding characteristic of pro-Duchampian, anti-Darwinian N’artists is their distain for using their own hands to create their work. This dismissive attitude is traceable directly to Duchamp who stated that he considered the execution of his ideas to be a boring activity. From the early 60’s when Warhol began his excursions into Duchampian Neo-Dada, we see a long history of postmodern artists outsourcing the execution of the work. While some might find this Duchampian conceptual provocation to be entertainingly rebellious, it has, in fact, led to a wholesale de-skilling of the artist and a dematerialization of the art object and, as such, is utterly antithetical to the cross-cultural definitions of art traceable back to the Pleistocene era. These long-standing definitions privilege art that requires specialized skill, contains emotional content, and gains significance from its place in the traditions of art.

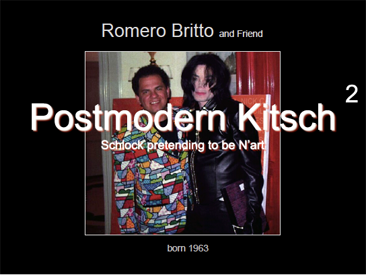

In such an environment it was inevitable that once Duchampian anti-art usurped the role of high-art that it would spawn superficial imitators who, while having no interest in the philosophical provocations of Duchamp, were nonetheless extremely savvy at taking advantage of the aesthetic vacuum that Duchamp created.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

No one represents this approach more blatantly than Miami’s own millionaire designer, Romero Britto. Britto has built a sizable branded empire of his own ($12 million is sales/year) using a horde of low wage employees to make paintings out of his sketches of smiling kitties, dancing clowns, and polka-dot palm trees in a style he calls neo-pop cubism. “His work is infantile, unchallenging, obvious, and empty.” Despite this fact, he currently holds a monopoly on public sculpture in Miami. Such is the legacy of Duchamp. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Obviously, the lack of aesthetics standards promoted in Weintraub’s essay is the substantive issue before us today but I did promise to discuss the bogus art of Thomas Kinkade before concluding, and so I will. The Thomas Kinkade’s brand reflects a series of formulaic themes that are intended to promote tranquility, joy, peace, love, and the beauty of God’s creation. Worthy goals all. Unfortunately, he doesn’t achieve his goal because he never really tries. Instead of the profound search for meaning, objectivity, and new experience that are essential for profound high-art, Kinkade’s work is about flattering his audience and reassuring its taste, its security, its interests, and its doctrinal morality. Kinkade’s images are visual valium, not high-art. His process is blatantly formulaic and, rather than being embarrassed by this fact, that he actually had the chutzpah to publish 16 guidelines for creating the “Thomas Kinkade look” ranging from using dodged corners and a soft-edges to create a gauzy, gentle feel, imbedding hidden references to Christian scripture and the names of his children, relying on a short focal length to direct pictorial interest to nostalgic elements of homespun simplicity, and, to top it all off, to imbuing the project with LOVE. In keeping with this last guideline perhaps we should redesign all curriculum so that every studio class starts with a group hug and a rousing chorus of Kumbaya. But I digress. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Thomas Kinkade died in 2012 - two years after I wrote this paper |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

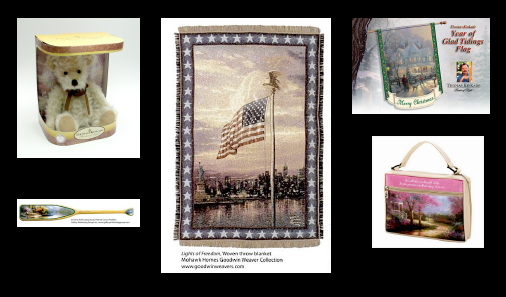

Samples of hyper-sentimentalized products available under the Kinkade brand |

|

|

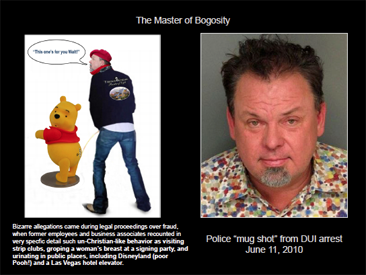

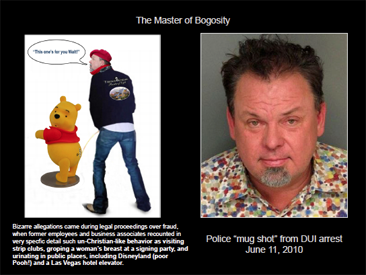

In contrast to his marketing of this Hallmark card version of LOVE, peace, and Christian family values, Kinkade’s personal life has somewhat a darker underbelly. Curious how often that is the case with moralizing posers. Kinkade has been found guilty several times of defrauding his franchise holders, he has been reported by his own employees as having groped a female fan’s breasts at a publicity event in a drunken stupor and as having urinated on a Winne the Pooh statue at Disneyland while saying, “This one’s for you, Walt.”

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

His frequently reported bouts of public drunkenness were recently substantiated when he was arrested for driving a motor vehicle under the influence of alcohol. While I don’t ordinarily subscribe to exposing personal shortcomings in the context of evaluating an artist’s work but given the fact that Kinkade’s personal message of tranquility, joy, peace, love, doctrinal morality, and God’s importance in one’s life are central to the promotion of his paintings, his character and behavior, sadly, simultaneously provide insights into his lack of personal and artistic integrity.

So, in answer to Linda Weintraub’s proposition, I do not want either Duchampian intellectual provocations or the formulaic “feel-good” visual Valium of Thomas Kinkade to infect my painting students. They are personae non gratae because the task of teaching students to care, of encouraging them to feel, of demonstrating the joy and satisfaction that comes from being constructive rather than deconstructive, of providing them the tools to actively respond to experiences that are beautiful and alive, and of instructing them on how to draw, paint, and compose is too challenging, too important, and too time consuming to allow their life affirming learning experience to be obscured and diluted by two mutually exclusive but equally destructive streams of virulent kitsch.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

SITE INDEX |

|

|

|

email: brian_curtis@mac.com |

|

|

| University of Miami Faculty Webpage |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|